ON THE OLDEST IMAGES NOW TO BE SEEN

AND THEIR PREHISTORY

New work analyses and investigation of theoretical consequences

By Sven Sandström

sven.sandstrom@kultur.lu.se

Published as edition on the net in 2015

www.svensandstrom.se

© Sven Sandström 2015

SUMMARY

The earliest known articulate expressions of human mind are not technical objects but naturalistic works of art – they are man-made images some 40 000-35 000 years old. These have been found in our days’ south western Germany. Among them two figurines are here studied in depth.

The one of these represents a being with human features in association with a lion’s head; two more similar figurines have also been found. The other shows a horse. Their naturalistic character is obvious, while each of them still l represent its own distinct modification – the one in a narrative direction, the other in a decorative way.

Humans cannot improvise the making of images just out of their genetic nature. So together these figures prove that there had already existed naturalistic images for quite a time when they were produced. And the rich as well as consistent shape of the former, together with the fact that there must have been a great many of the same sort, makes clear that even this specialised tradition itself, departing from a general naturalism, must have been about for some time.

The idea of an image as something separated from the other senses’ reports is nothing innate. It can only have risen in a cultural process, on the basis of observations, reflections and consultations.

Still, there is a huge step to take between mentally to possess the conception of “image” and being able to produce a physical image of something. Direct transition of a sight seems within reach only where someone observes a being or object to cast its shadow on a flat surface an considers the effect. When drawing a line with some tingling matter all along the outline of such a shadow – the silhouette – this result in a reduced but authentic representation of the object. Departing from such a venture it may be possible to develop more elaborate naturalistic images. Almost all images produced on surfaces after this early period and down to some 10 000 years before our time are presented within contours that can be seen as silhouettes.

But concerning the age of this naturalistic tradition there is nothing to support whatever conjecture we may make. Almost certainly, as just hinted, images in a wide sense had existed before that this process began. From times long before the arrival on earth of our species, the times of Homo erectus, some small stone objects are stemming that must be understood as referring to human figures. But their forms are extremely schematic, and it is as references rather than as depictions that they relate to that motive. In the present text, however, image for a principle will mean depiction in near analogy with reality. To emphasize that, these early achievements will be singled out as effigies.

Each image that one comes across from that epoch is probably just one single remaining out of a production of thousands and thousands. In that perspective the three representatives for the same type of male figure with a lion’s head indicates an important tradition. The other object to be scrutinized here is unique, the one with decorative features. But still it can equally well have been quite representative for a major production in its time. Together these to images reflect a wider range of production and supposedly also demand than for imagery.

In spite of the scarcity of matter for support, the possibility that these few cultural traces are representing an early prosperous and rapidly vanishing life situation for the humans, that, as we mean to know, only recently had arrived to our continent. But from only some millennia later there re no signs of division upon specialities among the imges that are available for us. At the same time as the naturalistic tradition evidently came down from this time and became decisive for the long epoch that followed, it may be possible to see these in our present perspective extremely early images as late products of a epoch of imagery that was approaching its end, and thus to distinguish the following entire late Palaeolithic production of images as an epoch of its own.

Naturalism was then in power for an immensely long time. But from around 10 000 years before our time examples of this tradition are scarce, soon to disappear out of sight. Instead images of a very different type from the following millennia are found in Spain. To some extent the previous tradition is reflected in these, but in overall shapes thee are of a radically different nature. Here the forms are extremely simplified and stereotype, figures are similar within different categories – and account for their respective functions on the one hand by distinct type features and rather than by true depiction on the other hand by gestures and positions. Their functions within the overall picture is symbolic (something that cannot be found in the earlier tradition) at the same time as they use the space for perspicuous interaction.

Unlike in images of the earlier tradition these new types of shapes together could present narrative scenes, and such ones of great vivacity. While the previous tradition did not presume language at all, the type of these images might even have needed the existence of a developed language for to emerge.

TOWARDS THE PREHISTORY OF THE OLDEST KNOWN IMAGES

Two images

Almost everybody now is familiar with the phenomenon of Palaeolithic images on French cave walls. They are not only to be found in southern France, but also in Spain and northern Italy (with one singe example also in England). But images of older date have been found in the Czech Republic, Ukraine and western Russia – and in Swabia in southern Germany, where the hitherto oldest known ones have been brought to light.

Among these, there are two images of surpassed age that usually attract particular attention also because of their relative completeness and fine articulation.1

One of them is known as the “Lion Man” from Hohlenstein-Stadel; it represents a standing figure the head of which is that of a lion. Carved out of the tusk of a mammoth and almost 30 cm high – by that one of the largest free-standing sculptures from the entire late Palaeolithic. It was found already in the 1930’s. Not far from where this Lion Man was found, more recently another small sculpture out of a mammoth’s tusk has been excavated, with the same general conception but without preserving so much and such a fine articulation as in the fomer. And still later there has appeared a third figure of the same sort, rather ruined, but coming from the same span of time as the others.

Each time that any one of the old remains from such an archi-archaic culture is found it is by just a marvellous chance. Thousands and even millions of similar or comparable objects may have vanished in earth after the past 35 millennia or more. Unless quite extraordinary conditions had saved them – as in the case of the known cave paintings. So, when in our time as much as three specimens of the same conception surved in earth this in itself gives a very strong indication that once there had been an important production of such figures.

All three Lion-men show an upright figure, the head of which appositely reflects the character of a mountain lion from that period – not through imitation of details, but by means of overall, intrinsic analogy. Their trunks are elongated, and together with their short limbs and vigorous postures, one gets a strong impression of a forceful being. Nonetheless, to the extent that they are preserved in respective specimen, the limbs have elbow and knees like those of a human, and in the same direction works the proud postures.

Even if the “Lion Man” from Hohlenstein-Stadel is the most complete of these three, even there several parts are anyhow lacking. Among other things its side to the right is fragmented, and not much remains from the feet. But the head is almost intact, and most of the left side of the body remains. The summary cutting technique is used with remarkable mastery, as especially in the head. Its stature is quite expressive, like that of a very resolute man, and the lion’s head in integrated so that it adds to the effect of a vital presence. The way the neck passes over into the massive shoulders is particularly interesting, because it is neither a human neck and shoulders nor those of a lions, but a well-adjusted synthesis out of mutual modifications .

|

|

| The Lion Man from Hohlenstein-Stadel | |

The subtle structural fusion of features and the modifications that one finds in this Lion Man result in a trustworthy presentation of a new creature in which qualities from both species are finely balanced. Modern cross-breeding could not have done it better. When ten-thousands of years later there once again appeared human figures with animal heads there was a major difference. Now it is question of two heterogeneous body parts abruptly put together.

All three Lion-men display the result of a synthetic idea, that could not have come about without quite complex intellectual strain and successive achievements. This must obviously – in a first realization, whenever this was made – once have been preceded by a process of modifying and fitting together features from both sides, and by that most probably also have demanded comparisons with similar parts of other beings. The complexity of the task and the multiple judgments needed in such a process might remind us of conditions of art in our time.

The mastery with which this integrated whole has been executed makes it an important work and by that reason it seems wrong to ascribe it to just skilful imitation of earlier models. In my view even a very resourceful forger would have overwhelming difficulties to reach such a result.

But even so, if we don’t venture to propose that “Lion Man” from Hohlenstein-Stadel had been the direct model for the other two, I don’t see any other possibility than to ascribe this achievement with its the seeming modernity in the intellectual process needed for this conception must to a common archetype further back in the past. This one not only reflects but also really carries consistent structures of an evolved mental culture. I have not come across any other in this way comparable artifact from these early times.

The creation of something substantial and unified out of the two heterogeneous models of a man and a lion presumes intimate familiarity with both motive elements. Doubtless, as well the originator of this conception as those who made the individual figures had observed the involved beings in real life. Mountain lions certainly were only too familiar to them.

*

For millennia then the general naturalism of the Lion Man as an overall conception of principle also characterizes the almost entire following production of images. While it at least seems sufficient reasonable to discuss this one as the oldest image unearthed until now, there is no possibility among the few images from this the very first period to single out any other work as coming next in time.

The other object for my scrutiny here, the “Vogelherd Horse”, in a formal analysis does not show any more specific similarity to any of the others, so i can not be proven to have been made later than any other known figure. The features that it has in common with the Lion Man are just general, but sufficient to allow the idea that they were contemporary – while its character anyhow is quite different.

Like most figures of this prehistoric tradition outside the caves this one is much smaller than the Lion Man – it hardly covers the palm of a hand – and it is a rather flat object. The two sides correspond almost entirely and have a naturalistic shape, each articulated with sufficient volume. In a formal analysis, however, they show differences in quality.

The Vogelherd Horse, facing left

The whole is presented within the comprehensive silhouette. Although the lower parts of its legs are missing, the rhythmical form of their upper parts makes evident that they are not just missing, but have been lost. The image is to be seen from either one side or the other– we certainly do not get complementary illusion of a horse in looking at it from the front aspect.

However, similar as these two sides may be, they are not identical, nor are they equally well articulated. In the aspect with the head facing left the form is consistent, firm and vigorous in character, with accentuated and continuous rhythms – features that points to an experienced maker with fine skills.

The shape and the relations between the parts on the opposite side are looser and less consistent. The conditions of preservation offer no explanation of this difference. So either this side has been finished by another person, or it has been left without a final articulation by its maker. Whichever, in combination with the rather flat form, these features raise the suspicion that it had been intended mainly to be seen from the one side.

The Vogelherd Horse, facing right

The mastery which I found in the articulation of its left-facing side manifests itself not least in the naturalistic accuracy of the horse anatomy. In the motive itself there are coverings for most of the beautiful rhythms of this body. At the same time the neck-and-head portion is given strikingly much volume. It should be noted that breeds of horses with very long necks indeed existed at that time. But after comparing this image with accessible paleo-zoological material, however, I must conclude that here this feature in fact must be judged somewhat exaggerated.

This circumstantial execution and continuity, the vigour of the overall shape in the representative aspect as well as the relative neglect of the opposite side together with the flat shape all work together in the same direction – in the execution of this figurine there has been a decorative intention present. Its character makes it apt for e.g. a use as a body decoration.

Within that what is preserved from the next following production I have not found any further modifications comparable to those in this figurine and the Lion Man. Of course the degree of illusionism of works varies quite a lot within the naturalistic tradition, but then mainly in being summary respectively circumstantial in execution – and of course also in individual hand-writing and skill, here very difficult to follow up because of the extreme fragmentation of the preserved original production. (More basic variation has occurred later – as with the “Venus from Willendorff” and similar figures).

There is nothing incidental about the modifications in these two works, however, these concern their entire characters and can be understood in relation to two different tasks within the culture – the one narrative and most hypothetically also cultic, while the other is that of decoration.

The sparse supply of images preserved from these earliest times certainly does not allow for any statistic deliberations at all. But it is still a remarkable fact that the mere type of modifications within an image occurs in just two of the very oldest images and then no more. It indicates an underlying culture with scope for differentiation in task, even beyond the necessities for survival. The present idea generally held about the dates of the entry of modern man on our continent, about 40 000 years before our time, suggests a rather short span of time between this major event and the production of these images. With all precaution this allows us to take into account the possibility that life conditions might have been favourable for the incoming people during that time. The lack of similar features within the production of images remaining from following years and millennia also opens for deliberations concerning the possibility that a harsh shift of life conditions had afflicted the humans here. Rather soon after these earliest dates the first Ice Age that our species has experience broke in, and it glaciers soon covered most of our continent north of the Alps. Still, all this together is something just to have in mind – awaiting further more substantial support for theory building.

When it comes to the relative age of those early images it is possible to develop more decisive ideas, even if this concerns just short span of time. Both are executed with apparent skill and as compact wholes without anything that can indicate hesitation. Today it is evident (by reasons mentioned here) that no human is able to improvise a naturalistic image – the ability to achieve something of that nature must be built up in mind and body in a process over several years. No one can make an image unless he/she has had sufficient access to images for to learn in imitating and varying their features and comprehensive characters. And this always takes some time. When it comes to image makers on the level that is discussed here the works witness of a more demanding background with years of preparation, probably with the teaching from some already skilled image maker, and also access to earlier produced images.

For any specific overall image character there must also necessarily have been more general conditions in current culture, such as demand for specific uses – while, as indicated, the space for differentiation in demand might have been related to the scope there had been left within the society for such production. However, unlike many earlier students of this matter, I do not presuppose specific needs within the society for to explain the rise of the one or other production of images – in mere human nature there is always scope for the ludic aspect, even for the ludic aspect in isolation.

In each of these just studied cases we must thus count with one already established way of conceiving that involves a specific modification in relation to a shape in physical reality. But when modifications themselves are about these imply more specific starting posiions, and in these cases this is one and the same, a consistent naturalism.

As a general and fundamental phenomenon naturalism must be ascribed equally fundamental conditions, developed within culture. This will be further argued here. And for two different brands of modifications to develop there must have been at least one generation of makers that already mastered a pure naturalism and then at least another that contributet to the internal consequence in the developed the deviations. That makes for a purely theoretical necessity of three previous generations of image makers. But the history of older art gives many examples of development for different artistic traditions step-by-step over centuries, while it is only in modern times under extremely different cultural conditions, that new traditions have risen in rapidity, if ever. These conditions permits us to take for granted that there was a tradition of a certain age established already when the Lion Man and the Horse from Vogelherd came about.

Naturalism in image making, among other things, of course is always presumed to be conditioned by studies of the nature and natural forms. But even so, the image maker is no camera, and the shape of an individual image may just as much rely on studies of existing images as on immediate observations of real life – yes, even rely exclusively on the former. As far as our experiences go there are no naturalistic images without owing very much to earlier production of images.

*

As to illusion of real life and body, in an image there is no difference between the two works that have just been under study. Both are highly naturalistic, and yet one can observe one specific modification in them. As discreet these may be, they are all the more important for their effect. And in both it is inconceivable that this could not have been brought about without a qualified brain labour. This achievement might have been performed long ago or recently. As to the Lion Man just because that the idea comes back tree times it is most improbable that it had been improvised just in view of any of these works. Even if it in the case of the Horse from Vogelherd were possible with an invention on the spot that would not seriously hurt the hypothesis concerning more than one deviation from the naturalistic stem that been divided.

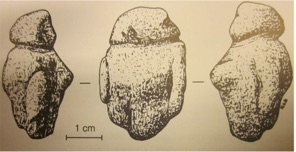

From the same early time a handful of other figurines are found , naturalistic but mostly rather worn by time and grinding earth. The two other lion-man figures are mentioned, very much of the same general type but both are in a poorer condition. Several of these are of the same general type as the Horse from Vogelherd - flattened but with volume in the bodies. None is sufficiently well preserved for to allow any close judgment for intrinsic qualities. Obvious modifications are not found in any figurine from this group. Nor it is possible to ascribe any of them an apparently decorative character, except for regular groups of notches, parallel lines and/or cross-hatchings over their trunks on some of them – just an extremely simple decoration. But we cannot take for certain that these elements stem from their production – the same sort of very simple decor is found on many objects from different times, however much they departed from each other in shape and date. It might thus have been added by owners and that can have happened long time after their production.

Two decorated figurines, rather damaged (the upper a mountain lion?), ivory, from Vogelherd

From the following ten millennia and more, in my experience, there are no finds of images that are distinctly decorative in shape or bear developed decorative patterns. With exception for the well-defined group of “Venuses”. When finally patterns of such a kind start to appear, they are completely different in nature.

*

For us the different specimens just discussed have to represent the very beginnings of Art History. But, as already elucidated, the real beginning of the Palaeolithic production of images must be looked for in earlier times.

If modern man really first had entered the European continent about 40 000 years ago, and the entry of humans on this continent happened around 40 000 years ago, the and the production of the Lion Man would have happened short time after the entry. This is one possibility, but hardly anything to count upon in the present state of things. Between the two events might as well have elapsed many millennia. Even so, while arguments of time are difficult to evaluate in this context, I think to that the indications for a previously developed culture of images that have been exposed here are rather basic to the mere phenomenon, and therefore more substantial.

In subsequent Palaeolithic production there is no division in character, and even if the. works differs very much as to degree of detail and elegance etc. between different objects, finding places etc., so is it only one single naturalistic tradition that is to be found there. It seems reasonable to emphasis this difference from the conditions for the older works, and thus project a first period of naturalistic imagery on those two specimens and further back onto their preconditions behind the shield of historical inaccessibility. If so, almost the entire late Palaeolithic production would constitute the second chapter of Art History.

*

Not long after this first period of human presence in Europe, represented by the works discussed, the Great Ice Age began, and did so very rapidly. Scarcity of food and other trials may have left less time for work that did not add to people’s chances of survival, and led to shrinking demand. While there is no given relation at all between the number of images found and the scale on which they were originally produced, it is still worth considering that very few images from the next following four to five millennia have been found. It might indicate a shrinking production. From about twenty-four to seventeen millennia before us, there are all the more preserved images – not to talk of the last seven or so millennia of continued production. In any case, as research currently stands, no important or consistent deviations from the naturalistic formal character of images have been presented. Ten millennia later the situation of formal conception is more complex. In between, a group of figurines with female traits have been found, of a deviating formal character, as a mighty parenthesis within the otherwise overall tradition.

Early and incomplete states of representing images

However, even if the history of naturalism must go back beyond the creation of its now oldest exponents that does not mean it to have been the very first and initial character for pictures. Among archaeological finds there exist a couple of small figures the shapes of which often have been interpreted as human, and that must be incomparably much older.

One of them, found in Berekhat Ram in Israel, has been dated to at least 230 000 years of age – with the possibility of being 700 000 years old. If made by a human hand, that one must thus have belonged to somebody from an earlier kind of our species. The object in question consists of a very small piece of stone with simple forms, two rounded portions of which could be understood as a trunk and a head (though in the later there fails even the

“Venus” from Berekhat Ram.

The least approach to facial features) – while the natural places for arms and legs, respectively, are occupied by parallel forms from the trunk, and along the sides and down. Moreover there protrudes an indistinct conic form reminding of female breasts from the “trunk”. The object is rather rough, and slightly asymmetrical. In contrast to this, symmetry is common in other and later non-naturalistic figures from very early times –any which, however, is extremely much younger.5

The other object that has been proposed to be our absolutely oldest image is a stone form that was found in Morocco, named the “Venus” of Tan-Tan after its find place. Its age has been estimated at a minimum of 200 000 years, with the possibility of it being anything up to a million years old. The shape of this object is almost symmetrical, and its similarity with a human shape, even if it not quite striking is at least worth considering – while there also are features that go against that impression – like the vertical line that divides not only the possible legs, but also the trunk. It ends at the place where a head is expected, and this is occupied by a voluminous but rather indeterminate form.

Why is it called a “Venus”? There are no indication of sex whatsoever. Is this a man? There are certainly millions of stones on earth that display human features while they still have come about by mere chance. And the fact that these two objects from immemorial times were found on opposite sides of the Mediterranean, with a possible difference in age of up to so many millennia, does not add to the probability of their having been made by human hands.

“Venus” from Tan-Tan

One thing, however, really convinces me of their authenticity – almost completely – in spite of that they hardly can be singled out among all the haphazard stones in the world, That is the condition that the forms replacing or representing their heads, so different they are, both deviate from even a schematic affinity with the human head. It is as if both tops were covered with sacks. Weak support from a purely visual standpoint, but nonetheless a possible support, provided by the fact that the heads are conspicuously blank - because the same remarkable feature is displayed on almost all human figures from the Palaeolithic tradition. Towards the end of the latter, there are some exceptions, all male.

So we cannot disregard the possibility that it had been for cultural or behavioural reasons that human faces were mising here, that they were positively were avoided. If so, it must have been a very robust and deeply rooted prejudice. the same remarkable feature

The schematic character of these two shapes recalls children’s drawings. At the age of four and five, most children's drawings on paper represent figures and objects – houses etc. – using seemingly haphazard forms. Jean Piaget has pointed out that they use sets of individual schemes to arrive at a major scheme, composing pictural elements, still in combination assign each other meaning, and thus may succeed in communicating the idea. The schematic approach corresponds to the developmental state of the brain at this age. (Soon enough the children are making more advanced pictures). It may then be tempting to lay stress on the immense age of the two figures. The conclusion is then that both the Tan-Tan “Venus” and the Berekhat Ram figure where made by members of the Homo erectus species, or possibly by an archaic Homo sapiens, seems unavoidable. In either case, their brain capacity was inferior to that of a modern human. If the limit of what can be achieved in picture by a four-year-old child is represented with congregations of schematic forms, then it is relevant to ask whether the same might have been true for adult representatives for earlier forms of humans.6

There is thus a profound difference between such an image and a naturalistic one. To keep the two types apart in the discussion, I propose the term effigy for the former type. Of course, even today any person can draw a similar figure without having specific training, and many of us can do no better. That does not make us more primitive. And schematic forms also appear in sophisticated modern art – sometimes constituting the formal structure of the work, while colours, relations, proportions etc. might be all the more articulate.

Naturalism presupposes the idea of an image

Effigies, then, are different from images such as they have been discussed here up to this point. As little as with most phenomena to which we almost constantly relate in our everyday existence, we tend to feel need for defining an image . As visual image we have it all the time before the eyes. Accordingly, startlingly few attempts have been made to describe that phenomenon in human minds. For people living within nature and in immediate and total dependence on in – like early hunter-gatherers –there cannot originally have existed any conception like that of just an image. There, all sense impressions came together, always with different strength and dominance – and they still do so in us today, for the most., Spontaneously the individual has had little reason to regard the apprehended sight as a separate phenomenon. Not even in situations where the individual turns all attention to the visual scene, or the visual side otherwise totally dominates the received data.7

The phrase that the image “is like a scale applied to reality” pins down the mirror aspect of the problem. It is one of the theses in Wittgenstein’s penetrating attempt in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus to capture the concept of image or picture for a function within the discursive-logical system. (Which did not succeed). To my understanding a reflection on a stagnant water surface is the only phenomenon in the prehistoric natural world capable of directing human attention to just the visual side of things as something special, as something sharing visual qualities with some matter - while still being apprehended when detached from the same – the mirroring of a present reality. From the apprehension of the reflected physical reality to the reflection in its purely visual appearance one may draw many possible consequences.

The immediate visual reality appears then twice, complete and almost identical, though one of the versions is reversed and lacking substance. Sometimes the mirroring is complete. Separate meaning for the phenomenon of pure visual appearance comes through consciousness of elements and wholes before one’s eyes and is ready to act according to that. In the mirror situation something is reproduced, and in a totally naturalistic way. I am strongly inclined to believe that the idea of an image arose within culture out of mirror situations with complete reflections, and that it was first after that this understanding had to be established – perhaps even long after – that the further idea of a faithful man-made reproduction could start.

According to this reasoning, efforts in the direction of material images, whenever these began to be produced, would have been inseparable from the idea of similarity; the pursuit of similarity must have been constitutive when there had started efforts to venture something like a material image. Naturalism is certainly not just one direction among others within visual art; it is to be understood as a condition that originally directed human endeavour in this area.

Imitating something from the real world, then, is in principle not only different from making an effigy, but rather the very opposite. The origin and development of schemes are achieved within mind; they rely on inner representations and don’t have need for individual direct impressions. To make a schematic effigy is feasible without having developed any specific manual skill, while it is quite impossible even to attempt a naturalistic image of something without a considerable amount of prior training. In such a training it is necessary to dispose a very specific combination of mental skills and neural abilities the complexity of which must be supposed to be far beyond what yet is possible to elucidate by brain science. Only theoretically this process could be imagined to happen within the life-span of one individual, but far more probable it is that the components have come up over millennia, step by step.

For an individual to make an acceptable naturalistic image it thus takes years of training, attempts to capture things and beings before the eyes, to understand and copy existing images, again and again. Hand and mind have had to learn to work on the same task and in near union. During such a development there has been established image-makers and/or exemplary images and possibly also an ambient society, supporting and/or demanding.

Visual images are intangible, and making an image means to work with the physical. The differences between the former and the later go all the way down to the ground. For mind and hand there simply does not exist any direct route to follow from something in the visual reality in shaping its material representation. It the first beginning (if such a thing can ever be postulated)to my knowledge there is only one phenomenon in the real world that shares qualities of absolute truth to reality with the reflection – and that is the shadow, cast of an object or being on a reasonably flat surface. As ephemeral as it is, and as depending on the situation, it anyhow leaves distinct and authentic traces of its material counterpart – and thus provide a transition from the world of mere appearances to physical reality. When cast on a solid surface, it is possible to draw a line with charcoal or other suitable material along the edge of the dark shadow of a figure or object placed between the light source and a flat rock or other surface. This represents an immediate transition from visual reality, but only in the outlines – it offers no elements of the enclosed body itself. But even a silhouette, especially as the profile of an object, can be quite sufficient to characterize the appearance of a wide variety of physical objects. And as sort of skeleton the silhouette offers better support fr further imitations of elements within the visual object.

That pictorial art had risen out of the study of shadows was a meaning expressed already by antique Greek authors. Most immediately it then may have been in relation to Egyptian art that this idea was then developed. The alternative that in antiquity one still could have been aware of the Palaeolithic tradition at present seems difficult to conceive.

The image makers of the late Palaeolithic did not just draw outlines when making mages. Even if the means used for filling in between these are summary, they are sufficient to let the figures stand out as living volumes, also bearing witness to direct visual observation of the living object – or/and imitation of earlier works from the tradition of imagery.

There may however also have been a separate formative tradition for figurines and sculptures – and even one with ultimate roots in the production type represented by the early effigies. And if so, we have then good reasons to believe also a plastic tradition on the way had offered supports for how to account for internal body forms.

Rhinoceros, drawing in the Chauvet cave, nearly 30,000 years old

Almost every Palaeolithic image displays just one single figure, most often that of a large animal. In the few cases when two figures appear together at least some have been added later. Within the entire tradition, to my knowledge, there is nothing like scenery with several figures. (Even if there in some of the most famous caves might seem to be something like a pack of animals rushing in the same direction. It is however a circumstantial effect – these are painted individually, often at different times).

The question why narrative compositions are lacking within the late Paleolithic imagery may be left for future findings and deliberations. If it arises here at all is because such ones started to be common in a somewhat later production of images in southern Europe.

Imagery reversed from visual re-presentation to animated symbolism

In the late Paleolithic imagery modern spectators often distinguish excellence and elegance in execution in combination with truth to nature. Some millennia after the date of the youngest examples we have of this tradition – not to take for a sign of its extinction–there appeared a new type of images at some places in Spain. That deviated distinctly from the earlier tradition as to qualities of draughtsmanship but also and above all in a more basic way.

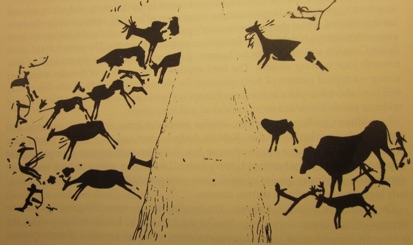

This applies with particular distinction for some extensive images with small figures dispersed in hunting scenes over roc surface within the Cueva de los Caballos in Valtorta, in the inland of southern Spain. They are very graphic – in both senses – and are to de found consistent ways of interaction. In the only form that they now can be studied, as they have been reported in about 1920 and reproduced in literature. Out there in the landscape there are now only small fragments left, however sufficiently much to verify that these reproductions are reliable.

If beings represented within the previously dominating tradition almost never were human, but while al figures there are presented alone and complete, all figures here are accounted for as just summary and dark shadow figures, while also together in great number. They are all accounted for in uniform colour and summary lines, but in a set of very different attitudes of action. The humans are mainly drawn as just lines.

Cueva de los Caballos, two scenes (fragmented) with hunters and animals

The lines in human representations here offer a striking opposite to silhouettes – and so far in a strictly stereotype form. The stereotypy of individual forms does not prevent the scenes from conveying a very lively narrative effect. The figures appear in changing and vivid positions, like gestures accounting for intense interaction in between themselves and the apparently hunted animals. There are several animal species around, each of which is accounted for in its own typical stereotype shape. In the different animal clichés are repeated almost identically even in their positions.8

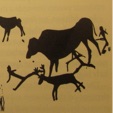

The silhouette, so important within the previous tradition, prevails anew in the animals here, but unlike the case with former it has a total dominance in these shapes, in also being filled in with just one and the same uniform colour (black in the depiction – but in reality red).

Here it is easy to distinguish In the animals here, it is easy to distinguish deers from aurochs and reindeers – not least, however, when comparing them with specimens out of the older tradition’s gallery of animals. One can thus not doubt of that the makers of these figures were acquainted with the older tradition of images – that which shows that they voluntarily had deviated so thoroughly from the latter.

Aurox Cave of Lascaux

So simplification and stereotypy in this production of images can hardly be taken for a simple sign of abandoned ambitions. Rather their characters have to be understood as consequences of an important shift of overall intention. What the new image makers had given up as to immediate illusion of living creatures, they had gained in an ability of which there are left no earlier traces – in the capacity of bringing forth vivid narrative scenes with several interrelated actors easy to apprehend in their typical reference and immediate tangibility. On the one plane more abstraction – more near to life on the other.

There is a fundamental difference between the two traditions, when it comes to content, “meaning”. Within the naturalistic tradition the images are offered for immediate recognition, each time as one stringently well characterized individuality, complete and isolated. Any evident content to be found there is immediately present and located within the sight, and concerns always physical features and connections. Whatever further meaning the spectator can reach depends either directly of the former or is just associations out of his/her own mind, and then another spectator might then think differently. In those works there is no trace whatsoever of symbols, and especially not in systematic interplay. Here in the younger tradition, each individual figure represents a category and carries its own reference to natural world on exactly the same conditions as all its equals.

It seems that this way of conveying meaning is something completely new in culture – at least to our present knowledge. Not only is it new in widening the scope of imagery to encompass narratives and scenic presentations, but it also and more primarily goes beyond previous imagery in preparing a totally new base for presenting meaning.

Even if these images are experienced as visual sights and in parallel to tangible life experiences, its figures has a character of signs as much as they have similarities with living beings; they use abstractions almost systematically in letting any figure represent one specific category and acquire individuality just in the part it plays within a complex scene. In functioning that way, being recognizable and representing categories and not individuals these can be seen as carriers of a specific symbolic system. Imagery in its visuality, but of the new nature, is still there for immediate grasp, and its expressive magnitude has widened by means for conveying meaning that it has in common with language. This, I think, is enough for regarding it as announcing a third chapter in the History of Art.

Literture:

Robert G. Bednarik, A figurine from the African Auchuleian. Current Antropology, 44 (3), 2003.

Jean Clottes, Cave Art, New York 2008.

Jill Cook, Ice Age and the Arrival of the Modern Mind. British Museum, London 2013.

Henri Delporte, L’image des animaux dans l’art préhistorique, Picard ed. 1990.

N. Goren Inbar & S.Peltz, Additional remarks on the Berekhat Ram figure. Rock Art Research 12, 1995.

E.Goldberg, The new Executive Brain. Frontal cortex in a Complex World. Oxford 2009.

André Leroi-Gourhan, Dictionnaire de la prehistoire, Paris 1988.

Louis-René Noughter, L’art de la préhstoire. Paris/Torino 1983.

Hugo Obermeier, Las penturas rupestres del Barranco de Valltorta, Castillón 1919.

Patrick Paillet, Les arts préhistoriques, Rennes 2006, p.33.

Jean Piaget & Bärbel Imhelder, The mental imagery in the child, New York 1971.

Sven Sandström, Intuition och åskådlighet, Stockholm 1996.

Sven Sandström, Explaining the Obvious, Lund 2008.

K.Weinberger, Der Löwenmensch. Tier und Mensch in der Kunst des Eiszeit, Ulm 1994.

NOTES

- Jill Cook, Ice age and the arrival of the Modern, p.30, 52.

- K Steinberger, Der Löwenmann.

This object was found in the 1930’s and presented to the Nazi hierarchy the widely used it in the propaganda for the idea of the pure and age-old Arian race. But there is nothing to indicate any fraud – while the existence of the two further examples of the same conception proves that the conception is genuine, and this would normally be enough for to accept them all. It has been dated out of the age of the geological strata where it reportedly was found – and this is in harmony with the conditions of the two others. Until now carbon-14-dating of the mere object has not been accounted for.

- Henri Delporte, L’image des animaux, passim.

- N. Goren Inbar & S.Pelz, Additional remarks

- E.Goldberg, The new Executive Brain - Sven Sandström, Explaining the Obvious.