ON LEARNING AND CONTINUING

THE PALAEOLITIC TRADITION OF ART

By Sven Sandström

sven.sandstrom@kultur.lu.se

Published as edition on the net in 2015

www.svensandstrom.se

© Sven Sandström 2015

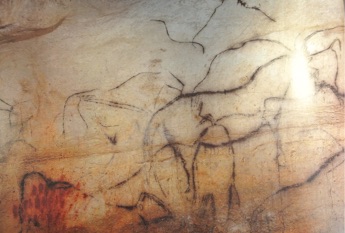

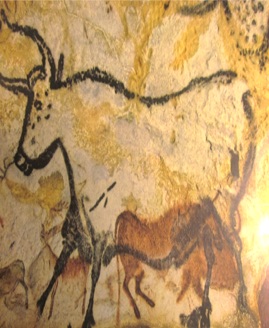

In the cave of Pech-Merle in southern France that I came to see for the first time five years ago there are numerous naturalistic line-drawings of horses and mammoths dispersed all over those part of the cave-walls that are sufficiently flat to fit for such strains. Sixty years earlier I had been happy enough to see the most famous among early art sites, the Lascaux, and had then succumbed to the impression of looking into one completely unified decoration, like a locality for some solemn task (a ”sanctuary”, to quote early scholarship). There could not have been any greater difference to the imagery of this cave that so far had been ratter unfamiliar to me. My immediate impression when entering was of something very much akin to a working space within a school of art.

Sometime later that association came back to me. I remembered a few spaces within that cave that had been especially cramped with line-drawings of horses and mammoths, partly incomplete, partly over-crossing each other – some of them being drawn with fine observation of the subject and very skilfully, other drawn less well, some of them even quite feebly articulated.

Drawings in the cave of Pech-Merle

As it appeared, once these drawings had been produced they have not been considered especially valuable when other image-makers needed space for new drawings. Just like you can see in an art school, where papers often are used again and again as long as it has been possible to distinguish the most recent forms. What one today sees there is almost a huddle of equally visible lines – but this must not have been true when there were people who still added their own drawing. The dark colouring matter that has been used there, containing manganite among other things, had come forth with higher brilliance when just applied on the cave wall than in lines that had been drawn there some time earlier. So the recent drawing had subdued the predecessors – but for just a short time. At least after a year or two that drawing had already lost lustre and sunk into the jumble of the other lines, appearing on the cave wall very much like we see it today.

That condition brings to the fore the aspect of dates of execution for the different images just mentioned or further to be discussed here. For most of them there has not been possible to obtain any indication of their ages at all. In most drawing material there is not enough carbon for any c14-date. In many cases two or more drawings side by side might as well have been executed with hounded of years in-between as the same day. However, there is sufficient of such evidence for to make clear that in all caves considered in this text there has been several visits of artists with long intervals. In this study it is anyhow sufficient for its scientific goal to deal with relative age and relations in terms of before and after.

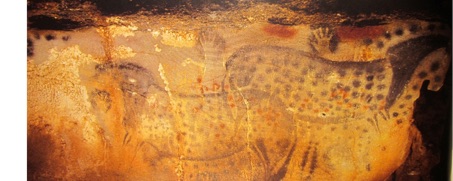

Further into the cave of Pech-Merle one finds part of the wall occupied with a rather extensive and at first glance somewhat bizarre imagery showing two horses turning each other the back.

The double-horse image in the cave of Pech-Merle

However, this is how that imagery appears today – it is highly probable that one of the two horses had prevailed in the moment that it was finished. By the same reason concerning difference between fresh and aged drawing-material that has just been discussed the effect of a double picture would have come about later on, when the more recent images had lost its lustre. As a matter of fact, there are even chemical differences between the materials of the two figures, telling us that they had come about on different conditions. (Lorblanchet 2010, p. 124 ff, 235).

The rear of the one horse is cutting into the same part of the other one. These two horses are remarkably similar, as much to the individual features as to their dimensions. Two horse-figures in a naturalistic conception. Both their heads are however curiously thin and minimal, very much deviating from normal horse-heads. Not least are their muffles directed downwards – in almost the entire tradition horse-heads point forwards. The condition of the head to the right may be due to that part of the cave wall to the extreme left seemingly had peeled away and with that also parts of the original head. Some decimetre further to the right, the rock itself ends with a sharp edge, leaving a portion just beyond the present minimized horse-head, happening to look very similar to a front contour of such a head. Over the two bodies but also beyond these there are dark dots dispersed, appearing not least in the just mentioned sharp-edged surface – with an effect that spontaneously can be seen to incorporate this part of the horses’ entire body. It is however out of question that the artist of the horse to the right would have utilised this rough form as part of his work – and in the other horse-figure there is no trace of it. The fact that the dots that cover both horses also are extended outside their bodies talks in favour of the meaning that these elements have come about after both figures.

While the two horses are so painstakingly similar, it has only been the one to the right that occupies sufficiently much space for its body on the wall. This provides a probable reason for the two horses’ rear parts to collide, and also for that the left figure has come about later, partly on the expense of the left one. Thus the former is to be considered a copy of the latter.

The copy did not appear as a perfect product when achieved, while the original was left molested by the act of copying, without allowing the copy to stand forth independently. The fact that the maker of the latter figure left his work with interferences of hind parts of the model does not permit us to believe that it had been brought about in the specific intention to produce an image for the cave wall. The only alternative that I can find is that the mere making of this copy might have fulfilled an important task, that the artist had performed in order to find out exactly how the original was shaped, thus to learn how to make such an image oneself. Study-copies with such intentions are well-known from art students within later western tradition. But this maker wasn’t just an art student, but an advanced artist in further training. (cf. Sandström, p. 7f).

This proceeding, if correctly reconstructed here, tells us something about the individual artists within the Palaeolithic tradition of art and how it was kept alive and brought forward not only in the normal chain where accomplished artists train younger adepts, but also from existing art works to artists sufficiently advanced in his/her trade to absorb the fine details of a predecessor’s work.

*

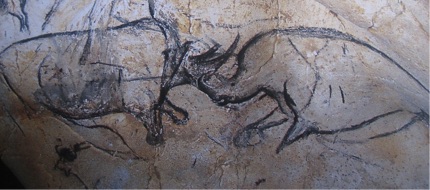

Among its rich variety of Palaeolithic images within the cave of Chauvet (see Clottes 2010) there is imagery with two apparently confronted rhinoceroses. For this specific imagery a very early date has been obtained. Other figures within the same cave have obtained much later dates. It is otherwise extremely rare within the entire Palaeolithic tradition that an image comprises more than just one figure. That condition calls for precaution not to take for granted that the togetherness here has been genuine. On the other hand, there are several smaller scenes in the same cave in which two rhinoceroses are confronted. So one can hardly doubt that fighting rhinoceroses really has been intended as a narrative theme. Within the Palaeolithic tradition of images there are a few further examples with a pair of major animals in confrontation; but this is exceptional.

Two rhinoceroses. Cave of Chauvet

The one rhinoceros in the image above might even be one of the very earliest wall-image that is left to us, with an age of about 30 millennia. However, it is just from one of the two figures that the proofs for deciding the date were taken. And they are so differently articulated that they clearly must be made with different hands. Already the fact that the rhinoceros to the left is drawn with more details talks strongly against this to have been the model for the other object of it is improbable that it would be made with the other figure for model. The figure to the right is more summary than the other, with a form that seems somewhat synthetic (however, the deformation of its hind parts in the picture above is just due to inequalities of the cave wall). Within the Palaeolithic tradition known to us summary shapes are frequent, contrary to synthetic outlines. At the same time as the two figures are different they appear to me reasonably equal as to the drawing skill. There is thus an obvious confrontation between two ways of drawing, not only between the figures of two big animals. If it hasn’t been question of just imitating an existing image this imagery still deals with focussing another work and with delivering a parallel. In this there is a pattern of interaction. Not between the artists, and not between the images themselves. But between the first image and the one who made the second one.

Like with the two horse-images in Pech-Merle the rhinoceroses appear in mirror symmetry; in the first case it is in meeting each other with the backs that the one figure mirrors the other; in the present case the animals are meeting front to front. The immediate proximity is required for the ”dialogue”, but the mirror symmetry is not the only way – as will be seen further on. There will be more to say here about mirror symmetry.

The theme with two opposed wild animals of equal size in mirror symmetry might have debuted here. It may be tempting to seek the origin of the later traditional heraldic versions of the theme here. But the distance in time between these cave-drawings and the first popping up of the latter in the ancient Middle West is too long and the idea is too easy to come up.

In the same cave of Chauvet there are two quite famous imageries featuring series animal figures, the one showing a sequence of horses (the anterior parts), the other one demonstrating the same part of lion-like animals. They are all remarkably well coordinated within the former, and turned in one and the same direction in both.

Even if it is hard here to find apparent differences in professional skills, as to the individual manner of drawing in each horse there are great differences, and differences there also are from an iconographic aspect. For example, the third horse from the left has a double line from cheek to ear, and the one to the extreme right is quite dark and has a ragged upright mane. In spite of their dense order no figure intrudes in the least on its neighbours – a remarkable display of discipline that must reflect some sort of cultural moments of interaction, repeated between the existing figures and the intentional approach of the individual makers. However how engaging – and possible – the idea of an immediate and constructive interaction between living artists may be, there is nothing to inform us concerning anything like that. There is no necessity that any encounter between the makers themselves has ever taken place; the image is the message, the existing row informs of the possibility to add one more figure. This sequence of horse images can have come about in some days or over centuries.

As far as I can see, none of those individual ways stands forth as exemplary for the others. The overall similarity between the figures is too general, and I cannot distinguish any specific quality, detail or all-over, that seems to have enticed other artists to repeat or to form any variance in their own contribution. To come about the straight coordination between the individual images has meant some understanding between the makers, either in immediate contact or more probably in that later coming artists had connected to the idea made visible on the cave wall. No matter the proceeding, this imagery still reflects as much one and the same cultural event within the Palaeolithic tradition of art.

Series of horses, cave of Chapeau

In any case, none of these images can have come about without attention to the already existing one, and inevitably they present themselves for comparison. Thus, even if the artists remain totally unknown, their presence as individual image-makers has been as strongly felt by the next-coming as it is to a modern student.

As to the dates we know that one of those horses was made more than 26 millennia ago, while for the others age is unknown. Here the aspect of chronology has little significance. More near at hand it is to depart from the successive overlapping. But the first horse in the row is the one to the right. And this one deviates especially much from the other figures in being entirely black and in have the mouth open – one sees its lower lip – as well as by its black colour. It is far from self-evident that the row had started with this image. No matter the internal order the series has grown in repeated relation. During the extensive period of time within which this imagery must have come about there races of horses relevant for this imagery lived in Europe – and the differences between the features of these horses might partly or entirely be explained by that the models have been of different kinds. But even so, there are equally evident differences in manners of drawing. Especially the third horse from the right stands forth with a smooth drawing manner and effect of volume.

When it comes to the swarm of lions within the same cave its immediate visual effect might be more of an event loaded with energy and aggressiveness, at least on a modern public. The big cats may seem to burst in together from the right. But several of them show obvious signs of direct imitation. The most adequate presentation here of a mountain-lion is doubtless the major figures in the lower right. As a matter of fact there is no other among those lion-heads that appears to have been drawn out of immediate studies of the natural forms – on the contrary, the majority of these heads exhibit rather irrational deviations – of course from how a real lion

The swarm of lions in the cave of Chapeau

looked, but more immediately from the first mentioned figure. The role of this as model or point of departure for the other figures is made clear already by different odd displacements of lines that are used in the first one for a naturalistic purpose. In this the outlines demonstrate a straight profile while there still are two ears to be seen. This is in exception from the otherwise totally dominating rule within the tradition to present figures in full profile. But these ears could be explained if the figure was meant to be seen from an oblique angle, something that occurs in other cave images of relatively late dates. In the two lion-figures just over the first one, however, there are not only two ears, but also two eyes together, in divergence from what can be seen in nature. To my experience these deviations from are unique. None among the makers of these lion-figures except for the one to the lower left seems to have been a really educated artist, but between the different figures it is easy to find differences as to the skills of their makers. Most of the figures occupy space near each other without intruding upon their neighbours – so far showing the same sort of concern that was found in the sequence of horse-images. But the pattern of the whole has quite another character; there are indications that several of the figures are drawn with the same hand, and in trying to develop something that deviates from immediate reality (which doesn’t say that the maker was aware of the unreality), they repeat much the same traces with variation. The other figures are less detailed and rather disproportioned – betraying a maker without much training. Maybe the figure to the lower right has been made before all others, but there is reason to believe that at least most of the other figures have been drawn within a short time by one person trying to develop something in supporting him/herself on the first image The less skilful figures add nothing to this while still relate to the same. They may not be to taken all too serious.

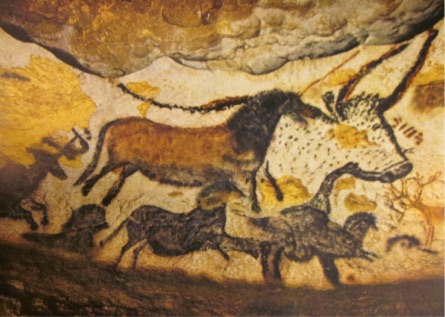

The very rich imagery in the cave of Lascaux offers many occasions for comparisons out of the same perspective of emulation, especially within the gallery of great animals with among other things several aurochses that dominates the central space of the cave. With some space in-between two of the aurochses there are confronting each other – and while the other animals of the same species that occur nearby all have individual features, the narrow relation between these two is especially demonstrated in their heads, where there appears a line across the mules that is lacking in the others.

(deceptively compressed image)

Heads of the two opposed aurochses in the central hall of Lascaux

There are some traits in the drawing of the animal to the left that talk in favour of proposing this one to have been the model; if so, the other figure is thus to be considered its copy. The eye is placed more in accordance with the natural position, the lines of the horns are more articulate, and the body that continues behind the head is enclosed with firm rhythmical outline where those in the other figure appear more uncertain. However, the other aurochses appearing in the drove of animals figuring over the wall are quite alike, which of course is to be expected from images made within a naturalistic tradition – but they are also deviating quite a lot as to formation and details from aurochses presented in other parts of the same cave, and beyond. Also here there are reasons to count with a distance in time between the individual figures, and like in the former case this does not preclude a continuous even if interspaced discussion in artistic matter between the successively present artists.

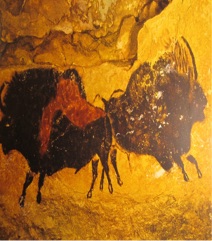

A bit away from the central space there is a constellation two bisons appearing in mirror symmetry -this time meeting at the butts. The one to the left prevails in the hind parts, so the order of coming about seems apparent. Most probably the original is most the bison to the right, the one with a massive black shape. That bison is drawn in a remarkably advanced way, in providing a sensation of movement that lacks in the other bison, that in turn deviates in being coloured, bi-crime. This difference might indicate just the intention to use the qualities of the older figure, but in modernizing its shape. In any case the difference reveals a taking stand and development, not just imitation. The use of more than one colour belonged to the relative modernity in parts of the imagery in Lascaux, while the cave also harbours not only this dark figure but also several other images drawn in just one colour, most often black or dark, as the case consistently had been with works of earlier times

(deceptively compressed image)

Two bisons in the cave of Lascaux

Why have some of the artists that have been active behind these situations of imagery turned their motives in reverse? It would perhaps seem more appropriate to repeat the forms in exactly the same order as in the original. The occurrence of original and copies together in the same direction within the two series in the cave of Chauvet might appear as more normal. This is a question beyond the intention of this paper that is to demonstrate interrelations between paleolithical artists through their works. But as this feature is so remarkable, it may provoke a lot of attempts for solutions. The field is open, but I might be allowed here to add a proposition of my own for answer. Today, it happens quite often with young people who are left-handed that they reverse their subjects, especially when starting to draw pictures. Right-handed people rarely do the same. Some perhaps the makers of reverse copies have been left-handed.

Sven Sandström 2015